I recently had the opportunity to provide a keynote presentation to a large audience of early years educators.

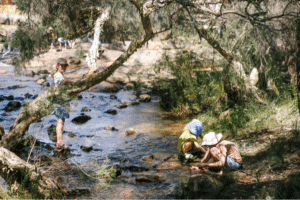

Amidst my talk which covered the physical, social, and emotional benefits of unstructured outdoor play for kids, and recent research on the educational benefits, I shared some photos of the best examples of play areas that I have seen in WA schools. None of them included award-winning playgrounds, but they did include child-made cubbies, scattered limestone blocks from a child-led deconstruction of an amphitheatre, a base camp with stones and gumnuts for currency as well as many natural elements like sand, dirt, trees, bushes, flowers, and uneven ground.

The photos got some quiet giggles because the spaces looked messy and possibly a bit 1970s. They didn’t look like the play spaces we might assume are the best for challenging physical abilities and inducing multi-age cooperation, collaboration, and expert-level communication skills. However, deconstructing an amphitheatre could not possibly be achieved without these. And the deconstruction was just the beginning. Only once it was deconstructed could the real imaginative, creative, co-operative, inclusive play begin.

Before I go any further, I need to clarify that I absolutely love and value the fact that we have so many playgrounds in schools and local parks. Playgrounds are wonderful structures for those who can use them. But it seems that somewhere along the line we started accepting false truths about what play spaces should be, which do not align with what research and experience tells us is most beneficial to kids and the community.

For example; I was recently contacted by a concerned community member who had witnessed their local council clear an expanse of bush to build a “nature playground”. In preparation to construct a nature playground, they removed the “nature” and the opportunities for kids to connect to it, play in and with it, and use all the skills I mentioned above. An installed playground, whether in a school or local government space, with no loose parts to move, create, collaborate on and feel ownership of is always going to deny kids the full experience and benefits of play. Research demonstrates this, and many of us can confirm it from our own childhood experiences.

Last week I was at the park with two groups of kids. The younger kids (aged 10) couldn’t believe their luck that a couple of small branches had come down from a tree. The grass was due for a mow which meant in some spots it was a bit longer and softer. They immediately went about getting a cubby sorted under the naturally shaped, old peppermint tree. They climbed the tree, then lay in the long, soft grass, balanced on wooden logs, and finished with some gymnastics.

The older girls (aged 16) sat at the shaded picnic table chatting, then moved over to the swings. One tried to squeeze into the baby swing, the second took the kid swing (still not big enough to be comfortable for many teenage girls) and the third sat close by. They chatted and swung until a lovely mum and toddler came over, then they picked up their phones and headed home. They knew they were playing on equipment that was meant for little kids.

The following day, the park was mowed. The branches, gumnuts, bits of stray bark and long grass all disappeared and so did the opportunity for the type of play the kids had enjoyed the day before. This was the week after all the new tree saplings were pruned to the same shape (lollipop).

I caught myself thinking how lucky it was that we were there yesterday, and then how absurd it was that we rely on lucky timing for kids to experience some branches, bark, and gumnuts at a local park. I also wondered how kids of the future will be able to climb trees when they are all shaped like lollipops.

I let my imagination run a little wild to explore the idea of councils deliberately leaving nature’s spare parts for kids to play with and letting trees grow into their intended natural shapes. I got really carried away and imagined an area with big swings and high spaces designed for older kids, separated from the little kid play area by some natural bush. I imagined how busy a space like that would be and how good the older kids would feel knowing it was for them and that they were welcome there.

The truth is my imagination isn’t even very good. I can’t imagine the spaces that the kids would come up with. I know from experience consulting with kids that their plans would likely cost less than most new playgrounds, and that there would be something for everyone. There would be many more oddly shaped trees, shrubs and flowers, a lot less uniformity and focus on manicured lawns, and there would definitely be water and some epically risky things to climb.

The school holidays are officially here. I wish all families luck in finding an un-manicured park nearby for some very valuable and developmentally important, cost-free play.